The Apollo moon landing was real, but NASA's quarantine procedure was not

NASA officials overestimated their ability to contain alien microbes after the first moon landing, a new analysis suggests.

In a small desert town, dozens of unsuspecting people suddenly drop dead from a mysterious plague. The infectious agent has come from outer space; it has no known cure, and the U.S. government must scramble to contain it before it destroys the world.

This is the plot of "The Andromeda Strain," a 1969 novel by author Michael Crichton. The book was published just two months before humans first set foot on the moon, and it sparked widespread panic about what the Apollo 11 astronauts might bring back. Luckily, NASA had a quarantine protocol in place for the mission. But those measures might have been largely for show, according to new research published in the science history journal Isis.

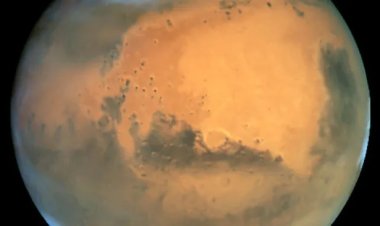

When astronauts first returned from the moon in 1969, NASA officials were concerned that they might carry some weird space microbes back to Earth with them. At the time, neither the US nor USSR had successfully returned a probe from the moon — let alone one with soil samples and actual humans aboard. As a result, nobody knew for sure whether or not the moon harbored microscopic life.

NASA set up a quarantine facility in Houston known as the Lunar Receiving Laboratory in order to counteract the possibility of any hitchhiking alien germs escaping onto Earth. When the Apollo 11 crew returned from their mission, they were immediately ushered into this state-of-the-art, multimillion dollar facility, where they spent three weeks. Twenty-four NASA employees who were exposed to lunar material as they helped the astronauts disembark were quarantined as well, the New York Times reported.

On its face, the quarantine protocol looked sensible. But the new research suggests that despite the money and resources invested in it, NASA's "planetary protection" efforts were largely for show. "The quarantine protocol looked like a success only because it was not needed," study author Dagomar Degroot, a historian at Georgetown University, wrote in the new paper.