How an Indigenous community in Panama is escaping rising seas

The Indigenous Guna peoples' relocation from Panama could offer lessons for other communities threatened by climate change.

In pictures from high above, the island of Gardi Sugdub resembles a container shipyard — small, brightly colored dwellings are jammed together cheek to jowl. At ground level, the island, one of more than 350 in the San Blas archipelago off the northern coast of Panama, is hot, flat and crowded. More than 1,000 people occupy the narrow dwellings that cover virtually every bit of the 150-by-400-meter island, which is slowly being swallowed by rising seas driven by climate change.

This year, about 300 families from Gardi Sugdub are expected to begin moving to a new community on the mainland. The resettlement plan was initiated by the residents there more than a decade ago when they could no longer deny that the island couldn’t accommodate the growing population. Rising seas and intense storms are only making the predicament more dire.

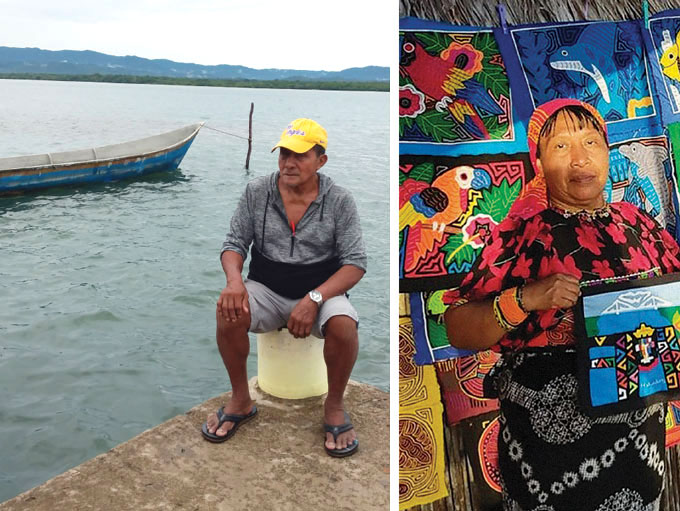

Many of the older adults will opt to stay put. Some still don’t believe climate change poses a threat, but 70-year-old Pedro Lopez is not among them. Lopez, whose cousin interpreted for him during our Zoom interview, currently shares a small house with 16 family members and the family dog. He doesn’t plan to move. He knows Gardi Sugdub, translated as Crab Island, along with many others in the archipelago, is going underwater, but he believes it won’t happen within his lifetime.

The Indigenous Guna people have occupied these Caribbean islands since around the mid-1800s, when they abandoned the coastal jungle area near what is now the Panama-Colombia border to establish better trade and escape disease-carrying pests. Now, they are among the estimated hundreds of millions of people worldwide who by the end of the century may be forced to flee their land because of rising sea levels (SN: 5/9/20 & 5/23/20, p. 22).

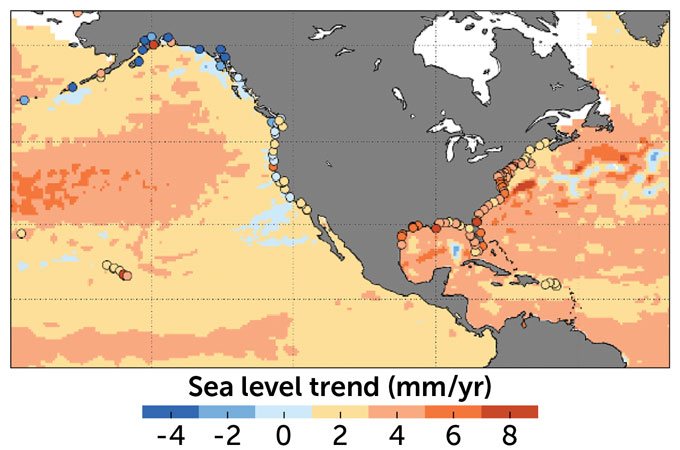

In the Caribbean, sea level rise currently averages around 3 to 4 millimeters per year. As global temperatures continue to rise, it is expected to hit 1 centimeter per year or more by century’s end.

All of the islands of the San Blas archipelago will eventually be underwater and uninhabitable, says Steven Paton, who directs the Physical Monitoring Program at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. “Some may need to be abandoned very soon while others not for many decades,” he adds.

Anthropologist Anthony Oliver-Smith of the University of Florida in Gainesville has studied people who are forced from their homes by disasters for more than 50 years. Around the world, he says, climate change has become a major driver of displacement, with people who have limited resources facing the worst of it.

The impacts of climate change — flooding, rising seas and erosion — are threatening the Tuvaluans in the South Pacific, the Mi’Kmaq of Prince Edward Island in Canada and the Shinnecock Indian Nation of New York. Half of some 1,600 remaining tribe members there still occupy a more than 300-hectare territorial homeland on Long Island surrounded by multimillion-dollar Southampton mansions.

The Guna relocation is being closely watched as a possible template for other threatened communities. What sets the Guna apart from many others is that they have a place to go.

Rising sea levels in Guna Yala

More than 30,000 Indigenous Guna inhabit the province now called Guna Yala, which includes the archipelago once known as San Blas and a strip of mainland. Most live on the islands, traveling back to the mainland to get water from the mouth of the river there, and in some cases to tend crops. Some of the islands sit several meters above average sea level, but the vast majority are uninhabited spits of land with palm trees, many only a meter or less above sea level.

So far, only the residents of Gardi Sugdub are included in the relocation plan.

The Guna people of the islands are sustained by the biodiversity there. The sea, mangroves and nearby mainland forests provide food, medicine and building materials. The men hunt and fish to provide seafood to the best restaurants in Panama City, and agriculture remains part of the economy. Guna communities elect traditional authorities known as sailas (“chiefs” in Guna) and argars (“chief’s spokesmen”), and they hold regular meetings to address community issues.

In recent decades, the Guna have moved toward an economy based on tourism and providing services to outsiders. They earn money supplying food, souvenirs and cultural artifacts to tourists but allow visitors to the islands only with prior approval from the sailas. Outsiders are not permitted to own property or operate businesses.

Carlos Arenas is an international human rights lawyer and an adviser on social and climate justice issues. When he visited Gardi Sugdub in 2014 as a consultant for Displacement Solutions, a nonprofit initiative focused on housing, land and property rights, he was tasked to assess the nascent relocation plans and provide recommendations. He was shocked to see the visible threat posed by the rising sea. “You cannot see much elevation,” Arenas says. “The level of exposure was extremely high, but they don’t see it necessarily that way. They have been living there for more than 170 years.”

Heliodora Murphy grew up on Gardi Sugdub and has watched the ocean rise higher each year. The 52-year-old grandmother doesn’t understand those who dismiss climate change in light of the growing physical evidence all around. Murphy, also speaking through an interpreter, recalls her father bringing rocks and sand from a river on the mainland to shore up pathways and keep their home dry.

Arenas says that some families face a daily struggle against the ocean. They build barriers that are immediately destroyed and have to be built again.

Some of the stopgap measures have been counterproductive, like filling in coral reefs to expand the land area. Reefs are a natural buffer against wave action, storm surges, flooding and erosion. Destroying them has only added to the peril.

Today, Murphy says, storm surges carry water into her small, ground-level home. “It’s very different than in the past,” she says. “The waves are so much higher now.” About two years ago, she decided she’d move with her family. “We can’t stay here.”

A history of autonomy

Historically, the Guna have had a level of autonomy rare among Indigenous people. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in what is now Colombia and Panama, the Guna lived primarily near the Gulf of Urabá on the northern coast of Colombia. The two groups clashed violently, prompting the Guna to abandon the coastal border area and move north into the jungle of Panama near the Caribbean. By the mid-1800s, entire villages had relocated again, this time to the San Blas archipelago.

Panama declared its independence from Spain in 1821 and became a part of Gran Colombia. Throughout the 19th century, the Guna lived independently according to their customs. That changed in 1903 when Panama broke from Colombia. The new nation attempted to assimilate the people living on the archipelago.

But having escaped Spanish rule centuries earlier and avoided Colombian authority as well, the Guna resisted Panama’s acculturation efforts. When the Guna couldn’t achieve détente through other means, they launched an armed attack against the Panamanians in February 1925.

The United States, having occupied the Panama Canal Zone since 1903, had geopolitical interests in the region and threw its support behind the Guna. That support forced the Panamanian government into a negotiated peace that allowed the Guna to continue their way of life. In 1938, the Guna islands and adjacent coastline were recognized as a semiautonomous Indigenous territory, Guna Yala. The Guna have maintained control of that territory since.

The Guna find a new home

The Gardi Sugdub residents first broached the idea of relocation in 2010. “They basically ran out of room,” Oliver-Smith says.

He describes the Guna as the Indigenous people in Latin America who have been perhaps most successful in defending their cultural heritage, language and territory. They initiated the plans for resettlement and made arrangements among themselves to set aside 17 hectares of property on the mainland for these purposes. The land, within the Guna Yala territory, is near a school and health center being built by the Panamanian government.

When Guna leaders approached the government, the Ministry of Housing initially promised to build 50 houses on the parcel. But it remained just that — a promise — until around 2014, when the Guna began to speak publicly about their situation. News of their predicament caught the attention of Indigenous rights organizations and eventually Displacement Solutions, which turned to Arenas and Oliver-Smith to evaluate the situation and offer recommendations about the best way forward.

Following Displacement Solutions’ first report in 2014, Panama’s Ministry of Housing agreed to build 300 houses, along with the hospital and school. But Arenas, who until the COVID-19 pandemic started had visited Guna Yala every year or so, says progress remained slow, causing the Guna to question Panama’s commitment to the relocation. The Guna leveraged support from international groups and members of the Panamanian government to get the project moving. “They were the originators of the idea of resettlement,” Oliver-Smith says. “And they kept it alive.”

Arenas estimates that roughly 200 of the 300 houses in the new community are complete. The cost for the houses, which are being paid for by the Panamanian government, exceeds $10 million, and the Inter-American Development Bank has invested $800,000 in technical assistance. The new homes will have cement floors, bamboo walls, zinc roofs, running water and full electrification.

Before plans to relocate began, many Guna had already moved to cities including Panama City and Colón for school, work or simply to have more room. Arenas expects that many more people already living in mainland Panama will likely join their families in the new community. People on other Guna Yala islands will likely have to move eventually too.

Murphy has already picked out her two-bedroom home for her small nuclear family of seven. Two daughters moved to Panama City years ago, and she hopes to see them more. But at around 40 square meters, the homes may not accommodate the typical multigenerational, double-digit Guna families. Lopez plans to stay on the island, letting the younger generations live in the family’s new home on the mainland.

To ensure that the ethnic and cultural identities they fought to preserve are not lost in the move, the Guna plan to develop programs to teach traditions and culture to the resettled generations. But even on Gardi Sugdub, younger generations seem less inclined to practice the traditional customs — like making and wearing wini (vibrantly colored beads worn around the arms and legs) and molas (intricately designed fabric dresses that have become a symbol of Guna life and resistance to colonialism). Murphy began learning the craft when she was 6 years old. She spends two months constructing each ensemble, which she sells to tourists for $80.

Oliver-Smith is optimistic about the relocation plan but worries that the Panamanian government has repeated some mistakes that have doomed projects elsewhere by treating resettlement solely as a housing issue. “You don’t just pick people up and move them from point A to point B. It is a reconfiguring of a life of a people,” Oliver-Smith says. “It has political, social, economic, environmental, spiritual and cultural dimensions.”

As is often the case when Indigenous and rural communities relocate, Arenas says, the government failed to make the Guna equal participants in the design concept. “The Panamanian government is trying to build a Panama City neighborhood in the middle of a tropical forest,” he says. “They have not tried to save a single tree of this beautiful landscape…. They removed everything. They tried to flatten the land because it’s cheaper…. It’s also extremely hot there, and the building materials are hot.” This increases the risk of failure, he says, because the houses don’t match the environment.

But Murphy hopes everything will be better. The new village promises dry land and more space. And perhaps returning to the mainland the Guna occupied nearly 150 years ago will lead to a stronger connection to Guna historical culture and traditions.

Oliver-Smith says the Guna are facing the challenge of resettlement with an intact culture and language that he hopes will be a basis for maintaining cultural continuity. His time spent with the Guna has convinced him that, as disruptive and devastating as resettlement can be, the Guna relocating as a cohesive group are perhaps best equipped to emerge intact even if not unscathed.

“Carlos [Arenas] and I asked an old, retired saila if he thought resettlement would change the Guna,” he says. “He said, ‘No. Individuals may change out of choice, but our culture is eternal. It will never die.’ ”